Apple Phenotyping: The Tools Every Orchardist Needs

In Episode 424 of Cider Chat, we dive deeper into the intricate world of apple identification, this time focusing on apple phenotyping — the art and science of describing apples by their physical characteristics. This is Part 3 of the three part series on John Bunker, renowned author, apple detective, and founder of FEDCO Trees. Expect a master class and experiential lesson as he shares his extensive experience and provides a valuable toolbox of techniques that for apple fans, cider makers and orchardist.

What is Phenotyping?

Apple phenotyping refers to the process of identifying and describing apples by their observable physical traits, such as size, shape, color, and texture. These characteristics, known as phenotypes, help orchardists distinguish between different apple cultivars. While apples may be genetically identical, they can exhibit slight variations based on their environment, making phenotyping a key skill for identifying and preserving apple varieties.

Why is Apple Phenotyping Important?

Phenotyping is more than just a way to describe apples; it’s a critical method for orchard care, especially for those looking to preserve historic and rare apple varieties. John emphasizes that understanding the nuances of the apples you grow allows you to ensure that your orchard is correctly labeled and organized. This attention to detail not only improves the quality of your cider apples but also helps preserve the legacy of historic cultivars.

Phenotyping also allows orchardists to confirm apple identities in cases where DNA testing isn’t readily accessible or when historical records are incomplete. Whether you’re comparing apples from different orchards or identifying a lost variety, having a reliable set of phenotyping techniques in your toolbox is essential.

Watch this entire presentation at Cider Chat YouTube

The Orchardist’s Toolbox: Key Techniques for Phenotyping

John encourages orchardists to keep a thorough record of the apples they grow, noting characteristics such as:

- Size and Shape: Measure the diameter of the apple and observe its overall shape (e.g., round, oblate, or conic).

- Color and Skin: Note the ground color (the apple’s underlying color) and any blushes, stripes, or russeting that appear on the skin.

- Stem and Cavity: Examine the length and thickness of the stem, as well as the depth and width of the cavity where the stem attaches.

- Calyx and Basin: Check whether the calyx (the dried flower at the apple’s base) is open or closed, and assess the depth and shape of the basin around it.

Episode Transcript

This is about learning to observe.

You want to look at an applelike you never have ever before

when this session is over.

Hello, my name is Ria Windcaller and Iam the producer and cider emcee of this

weekly podcast where we speak with makers,cider enthusiasts, and folks within

(00:26):

the cider trade from around the world.

Bringing us into episode 424 ofCider Chat, we heard from John Bunker

telling us that once we listen tothis episode, we're never going to

be looking at an apple the same waybecause we're going to be understanding

(00:47):

all the different parts of an apple.

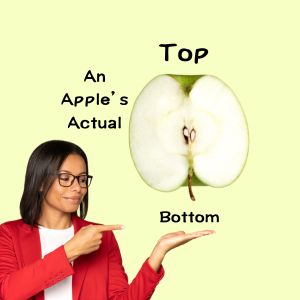

For instance, if you have an applesitting on the table right now and

the stem is going up, That appleis sitting there upside down.

What we thought was thebase is actually the top.

Everything's going to be kindof flipped upside down a bit,

but he has you so covered.

All the different slides thatare part of this presentation

(01:08):

are synced with the audio.

You're in for a treat.

So if you have an apple, grab it now.

This is an incredible lesson plan.

And John is out there as an amazingresearch, listen to his keynote address,

which was just a couple of episodes back.

She's really passing the torch here.

What if we were able to recordBeach and hear him talking about his

(01:30):

book or Downing talking about hislandscape work and work with orchards.

You know, we're talking about a hundredyears ago, but here we are in 2024, able

to have these recordings with a legendin the world of apples, John Bunker.

Yeah.

Now, for anyone out there in Cidervillewondering what's coming up on the

show, what's the fall gonna look like?

Well, we have a number of amazingepisodes rolling out to you.

(01:53):

In last week's episode, I had a littlesneak preview with someone from overseas

who we're gonna have on the podcast.

Yeah, just have to watch that episodeand see that little view there.

And then following, we'll have a little,another sneak peek here right now.

I'm holding a cider up to the screen.

This is from PrinceEdward Island in Canada.

(02:14):

This is from Red Island Cider.

And I'm really excited to try this apple.

We had a guest podcaster at RedIsland Cider speaking with the maker.

The two of them both attendedthe French Cider Tour in 2022.

So I'm sure it's going to be a hoot.

We'll get that all producedand ready for everybody.

So there's a lot going onand good times to come.

(02:36):

I hope the apples are abundant whereyou are or the cider cup is always full.

Either way, it's time now to grab aglass and enjoy this presentation with

John Bunker of Super Chili Farm basedup in Palermo, Maine, talking about

describing an apple phenotypically.

(02:57):

Today, I'm going to talk about howto describe an apple phenotypically,

which means by the physicalcharacteristics of the apple.

I've been attempting, and I say attemptingbecause it is very difficult to do, to

identify apples for about 40 years or so.

And one of the key things about it isto learn to describe an apple accurately.

(03:24):

That's what we're going to do today.

And what you're looking at now isan apple that is right side up.

In the U.

S.

and maybe in Canada,but definitely in the U.

S., we illustrate our apples upside down.

And if you look in particularlyolder European apple books,

(03:46):

they depict their apples rightside up, which means like this.

The slide is showing

The stem is the bottom of the apple,and the concave part, the basin,

on the opposite side, is the top.

The odd thing about the apple isthat the base, the base is at one

(04:10):

end and the basin is at the other,which makes it a little bit wonky.

What John is saying is that whenwe sit an apple on a table with the

stem going upright, We're actuallylooking at an apple upside down.

So the basin is at the apex, whichAnd the base is at the bottom, the

(04:33):

cavity is at the bottom, and so forth.

Why do we want to learn todo phenotyping of apples?

One is to get to knowthe apples that you grow.

, I would recommend that if you growten varieties or a hundred varieties,

that you phenotype all of them.

(04:53):

Draw a picture of them,take a photo of them.

And then describe them,learn to describe them.

What is the shape of the cavity?

What is the shape of the basin?

And so forth and so on.

It just helps you to know your apples.

Also, it's really, absolutelyessential to identifying apples.

(05:13):

Because, let's say you think youhave Gravenstein, and you don't know

Gravenstein as well, so you openup Dan Bussey's book or some other

book, And you read about it, it'slike, well, it's a striped apple.

But, if you read these texts, like TheIllustrated History of Apples in the U.

S.

and Canada, or, or Beach, Applesof New York, or whatever, they

(05:34):

talk about all these parts.

And that's the only way that you'regoing to actually be able to look at your

apple and say, oh, this is a winesap,this is a Gravenstein, except by sort

of general observation, because maybeyou've seen them so many times, you know.

But especially when you get into theones you don't know so well, it's going

(05:55):

to be how you identify your mysteries.

Also I'm involved in something calledthe Maine Heritage Orchard in Maine

and we're preserving rare historiccultivars and that's how we document them.

So, especially if you're into historicpreservation, that's really key.

(06:15):

It's also really importantwhen you're out in the field.

Because you can write down what you see.

And we can confirm and correct themistakes in our nurseries and in

our orchards, which is really, youknow, essentially identification.

But, but every nursery in the U.

S.

currently has mistakes in it.

(06:37):

There, there are no exceptionsand any nursery that tells

you otherwise are delusional.

The other thing is there's mistakes inevery collection and there's mistakes in

people's backyards and so forth and so on.

So we want to correct those mistakesor, maybe we want to correct them.

Also it's a way of standardizingand sharing your information.

(07:02):

With people you love, or peopleyou work with, or people you don't

know, but might be interested inwhat you're doing somewhere around

the country or around the world.

And we talked a lot yesterday about DNAprofiling, which is a big part of what I

do, but with the DNA profiling work, inother words identification through DNA

(07:23):

genetics, is only possible by comparison.

So that means what I call thereference panel, the database is

essential to doing DNA identification.

And the reference panel even hasmistakes in it, unfortunately,

which we're working on.

The challenge is to phenotyping.

(07:44):

There are issues around agreementof the definition of the different

parts and also how to describe them.

We'll talk about some of that.

And we're working, I'm workingwith others around the country to

streamline that and to find agreement.

Because if you look at the theclassic pomological books such

(08:07):

as Robert Hogg in England and S.

A.

Beach over here and, and Charles and A.

J.

Downing.

There's discrepancies in theterminology and in some cases they

use completely different terms todescribe the same characteristic.

So one of the things that, that is a realchallenge to this, but not insurmountable

(08:29):

are the discrepancies or whatever.

Also there's errors.

You might have a super rare historicPacific Northwest apple, for example,

and actually Bussey is wrong becausethe historical texts were relying

entirely on phenotypes and someof them didn't get it right either.

(08:51):

So that's a challenge, that you can workon with me in the future if you want.

And also the variability between applesfrom the same tree of the same cultivar.

Now these apples that you have in frontof you, does anybody know what this is?

Okay, this is Hudson's Golden Gem.

(09:12):

And if you look at each one of theseapples that you have, let's say you

have four in front of you, Each one ofthose is different from each other and,

you could get ten apples from the sametree of Hudson's Golden Gem and every

one of them is a unique individual.

Not genetically, they're geneticallyidentical, but phenotypically

(09:35):

they're a teeny bit different.

They're also different fromsite to site and year to year.

One of the things we're doing now istaking genetically identical individuals,

say Hudson's Golden Gem, we'll use that asan example, from different parts of the U.

S., and then phenotypicallydescribing them to see about

regional differences in phenotypes.

(09:58):

, I always start with my name or,you know, my initials and the date

and then the name of the apple.

Now, in this case, you can write Hudson'sGolden Gem, but if you don't know, you

use a unique identifier like today'sdate or you write the Smith Apple from

Walla Walla or, you know, whatever.

(10:18):

You come up with some unique thing.

So that when you put this intoyour pile of a hundred IDs and

you pull it out, descriptions,it's like, oh, which one was that?

So you want to have a unique identifier.

Then the location, we don't knowsome of this, so you could just use,

you know, whatever you want, but Iwrite down the location of the tree.

(10:41):

The road, the town, the county, thestate, these all are going to matter

both for your records and especiallyif you're going to try to do an ID.

Has anyone sent in anyapples for DNA profile?

Okay, so they give you a unique,a unique letter and number for

your accession that you send in.

(11:03):

If you've done that, thatwants to go on here, too.

And any synonyms.

You know, as far as I know, Hudson'sGolden Gem, , does not have any

synonyms that I know of, but I betgrowers, because it originated in,

in Oregon, it's not a super oldapple, but about maybe 80 years ago.

And and I bet some of the growers out herehave it, have their own synonyms for it.

(11:26):

But some apples, like Baldwin, thefamous Baldwin, is a good example

of, like, Forty or fifty synonyms.

So then the parentage, if you know it.

And the historical origin, if you know it.

And what does it resemble?

We'll get to that in a second.

And then a vintage.

In this case, it's a modern apple.

(11:46):

Some of these you're not going to know.

But what you know, you fill it in.

And you can make your own form.

What cultivar type doesit, does it resemble?

So this is really important, especiallyfor your own records, because if you've

got apples out in your orchard, youdon't actually even need to know the

real names, because you're callingit, , the red apple row 23 or whatever.

(12:10):

But it's really helpful, if youestablish a group of apples to which

you can compare for example in,these are ones that I use in Maine,

some of these would be irrelevant outhere, but , I've got Baldwin, Caville

Blanc is that super ribbedy one.

If you know it, Duchess is ripey.

(12:30):

Femeuse is almost solid red and soforth, but I've also included Red

Delicious and Golden Delicious.

And if I was going to say what does thisresemble just because I've never seen

it before and I'm just trying to remindmyself, I'd say probably golden delicious.

I mean, it's not, but it'ssort of vaguely resembles it.

So I might write in my notes.

(12:51):

Okay, so it's sort of resembles in shape.

It resembles Golden Deliciousor, or something, something

that you have in your head.

I, I did not bring aruler, which is a bummer.

But anyway, the first sort oflike description that we're gonna

do is the size of the apple.

And the size of the apple means thediameter, not the circumference.

(13:15):

And it means that the diameterat approximately the equator.

The diameter of Hudson's Golden Gem,we're just going to pick on Hudson's

Golden Gem, will vary depending on wasthe orchard has a lot of nitrogen, is

it a wild tree in an abandoned orchardthat you found, and so forth and so on.

(13:35):

But relatively speaking,it's a useful term.

And I I even put it in centimetersfor those that use centimeters.

Five centimeters for those of you that,that don't know centimeters is really

important because that's two inchesand under two inches we say is a crab

apple over two inches we say is not.

(13:56):

So if you want, you can, you can sortof guess obviously we're not looking at

small or very small and I'd say if I hadmy ruler on me, we're looking at probably.

Medium or medium to large.

Then I write down the shapes of the appleand every apple has multiple shapes.

(14:17):

This is also tricky when you get intoidentification because apples if you

read the historic texts, they'll say it'sroundish, oblate, and sometimes conic.

, is that a help?

Yes, it is a help because you're goingto identify apples and describe them in

their totality, not by one characteristic.

(14:40):

Although,

I've never seen a West Coast Hudson'sGolden Gem before, but we grow

it in the East, and ours look alittle bit different, but as soon

as I saw this, I knew instantlyit was a Hudson's Golden Gem.

And that's just becauseI'm familiar with it.

And we talked about that yesterday.

Also, that certain apples, especiallythe ones you come across a lot, you're

(15:02):

going to want to know them instantly.

And you don't even needto know why you know them.

You just look at it and yougo, Hudson's Golden Gem.

But in this case, this apple isconic, and it's also a little bit

ovate, and it's definitely oblong.

It's not roundish.

(15:24):

Now we're getting into stuff that is notso intuitive if an apple is regular or

irregular, is when you look at it with thestem facing you, like the bird's eye view,

. When you look at an apple like this,and it's round, that means it's regular.

And that is a very useful tool.

(15:45):

And that's a great term becausewhether the apple is cultivated

or uncultivated, it won't matter.

This is something that if anapple is irregular, many of them,

most of them will be irregular.

Now another thing that I didn't, maybeI mentioned it or maybe I didn't, the

reason why you have four apples infront of you, if you do, I hope, or

(16:09):

three, or, you know, I like to have 12.

is because then you can see thecommonality of the cultivar.

So, if you have one apple like, if Ijust have this, and this is the only

one that anybody's handed me, and I'munfamiliar with Hudson's Golden Gem, I

(16:29):

might wonder, well, is this an anomaly?

Are they usually rounder, orare they usually more oblique?

You don't know, but if you have10 of them, or 4 of them, or 12

of them in front of you, some ofmy friends, they like to have 20.

So they can just lay them out, andyou just see, okay, this one is, it's

a conic cultivar, or, or whatever.

(16:52):

So when an apple is ribbed, andyou can see that on the right

here that is called irregular.

And if you see it oval from the top, wellactually from the bottom, from, from the

stem end, it's also considered regular.

The most famous irregular applein North America, Roxbury Russet.

(17:15):

So then we have the overall color.

The overall color in this case, thisis from a farm stand in New York City.

Where they have two famous apples.

They have the red applesand the green apples.

So the overall color isincredibly deceiving.

Again going back to the classictext, like Beach or Hogg, they

(17:38):

will, say That Red Delicious.

They'll call it a yellow apple.

And the reason why they call it a yellowapple is because of the ground color.

The ground color is like thecanvas before you paint it.

When I was first getting my apprenticesinto helping me with this, They

(18:00):

would describe apples using classictext, and I'd look at something like

Baldwin or, you know, whatever, andthey'd say, it's a yellow apple.

I'm like, what?

No, this is not a yellow apple.

And then I'd, and I'd look, oh, I getit, because the ground color is yellow.

So you'll read an old description,it will say, a yellow apple

(18:22):

almost entirely covered with red.

So, the overall color, to me, hasnothing to do with the ground color.

It just is your impression.

So, Hudson's Golden Gem, it's notperfectly this way, but I'm going to

say what it is, it's a russet apple.

Is it 100 percent russet?

No.

(18:43):

But, what is your overall impression?

It's russet.

Many apples, any apple, you cansay red stripe, you know, maybe

that's your overall impression, ormaybe purple or pink or whatever.

But you also, again, add for yournotes, you want to be able to go

back and go, Oh yeah, that wasthe pink one or, or whatever.

(19:07):

So the ground color, is what'sbeneath the stripes and the blush.

And here we have one of the mostfamous historical apples of the

entire world in North America calledDuchess, or Duchess of Oldenburg

in Europe sometimes Borrowinka.

But this is technically a light yellowapple or light green apple, but I

(19:33):

would never write that when I waswriting down my overall impression.

I would call this a redapple or a red striped apple.

the skin can have stripes or not.

Now, genetically, stripes and blush,so, so in this case, and The St.

Lawrence, which is a southern, it'sa like Quebec apple or Nova Scotia,

(19:58):

New Brunswick very old historic apple.

It is very stripey.

Brock, which is a relativelymodern, about a hundred years old

apple from Maine, is not striped.

It is only blushed.

We'll look at blush in a minute.

Stripes and blush.

are not genetically the same.

(20:19):

They are determined by bydifferent alleles or whatever.

So an apple can bestriped but not blushed.

It can be blushed but not striped.

And we're going to learn more in a second.

here's Harrison, which is not blushed.

Now, maybe sometimes Harrisoncan have a very light blush,

(20:41):

but not in my experience.

Winter banana, which is oftengrown in the Pacific Northwest or

was historically as a pollinizer.

But it's a historic apple frommaybe Ohio or someplace, Indiana,

maybe, and was grown traditionallyin the East Coast as well.

It is a blushed apple.

(21:01):

And once you get to know winterbanana you will see it, you will know

instantly, cause, cause that rightthere is a very typical winter banana.

here are two apples thatare striped and blushed.

So I said that genetically stripesand blush are two different things,

they are, but an apple can have both.

(21:23):

So, in this case.

The blush is under the stripes.

So sometimes, when you look at anapple it definitely has a blush,

and the stripes are really cool.

They're sort of likedarker red or whatever.

Sometimes they kind of blendin like this Yarlington Mill.

But sometimes they're a little morepronounced like the Ashton Bitter,

(21:45):

but sometimes they're very pronounced.

Some apples have a bloom.

And a bloom is, from my understanding,, the literature is a little nebulous

about it, but I believe that it isa yeast on the skin of the apple.

This is Blue Pearmain, which isone of the most famous heirlooms

(22:07):

, of the American Northeast.

And if you look just to the right of thatscar on the fruit, the fruit looks blue.

It looks sort of purplish blue.

And that is this sort of dusty film,which is called bloom, which is on

many purple grapes, and many highbushblueberries, and lowbush blueberries.

(22:29):

Many plants have it includingsome apples, not a lot, but some.

But if you see it on an applethat's a really good, if you're into

identification, that's really a great,a great piece of information to have.

Some apples obviouslyhave russet, some do not.

Russet can be what I call a netting.

(22:49):

Over on the left, we have Gray Pearmain,which is on apple that originated Maine.

It's a really delicious dessert apple,and it sometimes does not have russet,

but about 85 to 90 percent of thetime it has sort of a net, you know,

sort of a netting of russet on it.

Roxbury russet, which is in the centerhas patches of ground color, which in

(23:14):

the case of Roxbury russet is green.

And then it has patches of russet.

I've been working on attempting to sortout the different golden russets lately.

This one, which is probably goldenrusset of Western New York, was

probably the most sought after.

But the russets, the golden russetsare, are really screwed up in the

(23:38):

nursery industry and historically.

Currently we call this GR1.

And GR1 is almost entirelyRussetted so then we have the dots.

Some writers call themconspicuous or inconspicuous.

And some call themprominent or not prominent.

And they mean the same thing.

(24:00):

And this apple on the left,which I photographed at Geneva,

And which I just totally love.

I don't know what it tastes like, butit is just so incredibly beautiful.

Has very conspicuous or prominent dots, asdoes the Vermont Historical Apple Stone.

The dots can be prominent, butthey can also be abundant or not.

(24:25):

Here's the Cox's Orange Pippin.

This was also photographed at Geneva.

But the the dots would be calledprominent, not super prominent.

One thing about the abundance ofdots, most apples, if you look

super closely, They are reallynumerous because they're so tiny.

(24:50):

But what we're talking aboutis what is sort of like visible

when you just kind of look at it.

If we look at our Hudson's Golden Gem, Iwould say they are incredibly numerous,

but they are not at all prominent.

So if you held this apple arm'slength away from you, you could

almost say there weren't dots on it.

(25:12):

Even though if you look closely,there most definitely are.

Here's another Vermont historicapple called Bethel, which is

really famous for its abundant,numerous and conspicuous dots.

So the dots come in different colors too.

Looking at our Hudson's Golden Gem Iwould say that these dots are either.

(25:39):

They're not white, they're not, they'renot gray, that you could say they were

russet and you could say they weretan, but you can write down, there's

not really like multiple choice here.

It's what do you see here in those dots?

This is about learning toobserve, you want to look at an

apple like you've never have everbefore when this session is over.

(26:04):

Redfield one of my favoriteapples has white dots.

Some apples have really white dots.

They're just so white and so forth.

Stone that we just looked ata minute ago has russet dots.

Dots can be small, medium, or large.

We have Benet Rouge that hassmall dots, Beauties of Wellington

(26:26):

and other Maine heirloom.

With medium and ombrophila anothersmall apple from Geneva has large dots.

My apple here, my Hudson's Golden Gem I'mlooking at, I would call those dots small.

The dots can be rough,sunken, stellate, or areolar.

(26:48):

This is really geeky stuff.

The rough dots, you can feel them.

You can close your eyes and run yourfinger gently over the surface of

your apple and you can feel them.

It's a really good descriptor.

Some of my dots here on one part of myHudson's Golden Gem are a teeny bit rough.

But especially where the skin issmooth, Where it's not russeted,

(27:10):

and then I can feel the rough dots.

But overall, I would not call these rough.

My apple that, one of the applesthat I've discovered in Maine

Windham russet, super rough dots,like when you, when you feel it.

It's like anyone, even somebody that hasnever hardly looked at an apple except to

eat one from the grocery store, would runtheir fingers over it and go, Wow, those

(27:34):

dots are, those bumps are really rough.

Povishon also, also rough dots.

So they can also be submerged.

This apple, which I callBitter Pew it's a seedling.

I brought scionwood this morning.

Some of you got it.

The dots look like they'reunderneath the surface of the skin.

(27:56):

And that's what it meansto be submerged or sunken.

It's almost like there's glass over them.

And you're looking through theglass into the dots that are,

that are underneath the skin.

Our Hudson's Golden Gem,definitely not sunken or submerged.

The dots can be areolar.

(28:17):

Areolar generally means thatthere's a darker part of the dot.

In the center, and it'ssurrounded by a halo.

So think like, you know,the Bible or something.

And and there's a sort of alight hazy color around the dot.

And in our case, these you couldalmost call areolar, but what I'm

(28:41):

seeing is a sort of a tan dot withkind of a little russet halo around it.

So you could call it areolar.

Stellate, I did not take a photoof stellate because they're really

hard to find, really hard to see.

But stellate means star shaped,and occasionally you'll find

dots that are star shaped.

(29:02):

This is northwestern greening ithas like a dark part, and then

kind of a glowing halo around it.

That is areola.

Here's our apple, right side up.

The base, which is where we'regoing to go next, which is the

cavity, which is the stem end.

The base is the base, not the basin.

So the stem can be small,medium, or, or long.

(29:25):

And at some point, we're actually going togive people as we start to digitize some

of this stuff, we're gonna see if we cancome up, proportion of the depth of the

cavity, which is the depression aroundthe stem, and the length of the stem.

But right now, we're just looking atit and saying, Ah, it looks short.

(29:46):

Ah, it looks medium.

Ah, it looks long.

So, Golden Delicious, really long stem.

Hudson's Golden Gem, I call that long.

That's a long stem.

The stem can also be variable, you cansee my Golden Delicious in the center.

My Red Tip, which is a MalusIoensis, has really long stems.

And if you look at it, those arefour random apples of Red Tip.

(30:09):

They're all really long, butbecause of how the apples grow

in the cluster, some apples canbe shorter or longer than others.

One of the instances where havingmultiple apples in front of you, if

you're describing them, it's really handy.

The other thing is if you get commercialapples, like let's say , you're

(30:30):

practicing and you say, okay, I'mgoing to go to the grocery store.

And get a bunch of different, becauseyou can go now and get, you know,

six or eight different varieties.

They're all, mostly all modern,but it can be fun to do.

But a lot of times now, they clipoff the stems which is a bummer.

But if you go to a farm stand or ifyou grow them yourself, you can usually

get them with the stems still on them.

(30:51):

In some cases, the stem isnot a defining characteristic.

I don't know Cosmic Crisp well enough,but I bought those at a grocery store.

But some like like pound sweet upthere, which is also known as pumpkin

sweet in some areas, always short.

And you'll get to know that.

So you'll get to know that thatsome apples that you find, eh,

(31:12):

you know, the stem is like notreally a defining characteristic,

but others really defining.

the stem can also be clubbed andsome have a big lump on the end.

And that means they're clubbed.

And some can be what we callbrachiate, which means that they have

sort of a lump halfway down, likea snake tried to digest a rabbit

(31:33):

and it got stuck in its throat.

The cavity is thedepression around the stem.

All pomological books, alldescriptions will talk about the

cavity, it's , like a term that you.

That you need to know.

And the cavity can benarrow, medium, or wide.

(31:54):

And again we can In the classictext, they don't define that.

But we're working on waysthat we can define it.

And also, like, Where is the endof the cavity and the beginning

of the shoulder or whatever?

It's a nebulous thing.

But some apples, thecavity is really narrow.

(32:15):

It just looks really narrow.

And others look really broad and wide.

So it's worth noting what you think of.

And I would call Hudson'sGolden Gem narrow to medium.

And that's also okay to puntand say narrow to medium or

medium to wide or, or whatever.

Here's Ben Davis, whichis classically narrow.

(32:37):

Wolf River, classically wide, andWilliams Pride, somewhere in the middle.

The depth of the cavity, canbe shallow, medium, or deep.

And again, we're talking subjectivehere, you could also do this by

looking at the apple cut in halfbut , some of them you look at and

(32:57):

it's like, ooh, that is really deep.

And others you look at andthere's, and it's non existent.

Some have virtually no cavity at all.

I would call my Hudson's Golden Gem hereprobably medium, somewhere around medium.

This is one of the first kind of weirdtechnical terms, but very important.

We have the slope angle relativeto the stem if the stem was

(33:23):

perfectly straight upright.

If it is a gentle sloping,we call it obtuse.

If it's medium, we call it acute.

The obtuse is like the bunny slope, ifyou're a skier, the accumulate is like the

double black diamond, if you're a skier,and the acute is somewhere in between.

We think of acute should be thesteepest, it's not, it's the in between.

(33:47):

So our apple here is is somewherebetween acute and accumulate.

So it's pretty steep.

It's not as steep as theycome, but it's pretty steep.

It's, it's bordering on acuminate.

The cavity can also be lipped.

Yellow Bellflower doesit pretty typically.

Pewaukee, if you know Pewaukee,does it like, sometimes 50 to 60

(34:09):

to 80 percent of the apples can be.

These are two small apples, thisBean and Ann Trio, both from Geneva.

Those are definitely lipped.

The cavity can be russeted or not.

So you know, we talked about russet.

For some apples, it is a defining feature.

(34:31):

If the cavity is russeted.

For some, it's sort of, occasionallyit is, occasionally it isn't.

The Chisel Jersey, fairly russeted, andthe Silver Cup down below and a local

seedling that we have in our neighborhood,which is which we call Everett Cunningham,

which is a silver cup lookalike, but it'sa old, old seedling, those heavily russet

(34:54):

and very much a defining characteristic.

Wolf River, if you know WolfRiver it is 98 percent of them

have a huge russet cavity.

There's others, red astrican, if youknow red astrican, always very russeted.

Many apples, never.

So it's a, it's a very handy descriptor.

(35:18):

Some apples are greenish around the stem.

And that's also really handy to know.

Cortland, which is very popularin New York and New England Almost

always has not russet around thecavity, or in the cavity, but has

a greenish patch, as does Liberty.

Now we'll go to the basin.

(35:39):

And again, we have ourapple right side up.

The basin end is at the apex, andit is the location of the calyx.

And the calyx is the dried flower.

The calyx can be small, medium, orlarge, and it can be open or closed.

(36:00):

And when it's closed,you cannot see into it.

The calyx lobes are verytight against one another.

And many apples are that way.

And one of my Hudson'sGolden Gem is closed.

One of mine is partly open, andtwo of mine are definitely open.

(36:21):

When they're open, you can seeright into, you know, you can

look into the heart of the apple.

You can see right inside.

So this is variable, at least, youknow, what we'd want to do , if

we were writing a collectivedescription of Hudson's Golden Gem,

you know, , because Dan Bussey'sbook wasn't complete or something.

(36:42):

We would, we would alllook at our calyxes.

We'd write down how many there were andthen we would come up with a number like,

you know, 80 percent are open or whatever.

And then we'd say, okay, wecould say it's an open calyx.

Some calyxes, like a Nehou andKingston Black, I'm not familiar

(37:06):

enough with either variety up tohave seen thousands of them, but the

ones that we have very much open.

The calyx lobes , are the little remnantpetals around the perimeter of your calyx.

This is one place where the classicwriters all invent their own terminology.

(37:30):

Some call them narrow, somecall them wide, some call them

upright, we have two terms here.

Flat convergent or erect conversion.

We have Connivent.

Connivent means that they rise up and thenseparate or reflect where they lay back.

flat on the apple.

These are mostly erect, andmine at least, are divided apart

(37:56):

and split away from the center.

And that would be a little,it's not perfectly conniving.

But it is sort of conniving.

This is like pretty geeky stuff.

And the writers all quarrelwith each other about this.

The most, useful thing about thecalyx lobes or the sepals, sepals,

(38:20):

is that, is it open or is it closed?

Because that, that isoften a defining feature.

The basin can be shallow, medium, or deep.

Here we have Vilberie.

Quite shallow, Yellow Transparent,a little less shallow.

Blue Pearmain, a little moredeep, and Cosmic Crisp, very deep.

(38:41):

So my Hudson's Golden Gems,here, I have four of them.

I would call themshallow to almost medium.

So we have the depth, then wehave narrow, medium, and wide.

We have Alexander, which is one ofthe parents of Wolf River, as narrow,

(39:02):

Hubbardston, Nonsuch, famous Massachusettshistoric apple, medium, and that Granny

Smith, look at how wide that basin is.

I mean, that is really, really wide.

The slope of the apple intothe basin can be steep.

Or it can be gentle.

(39:23):

And when it's gentle, we say it is obtuse.

When it's steep, we call it abrupt.

We do not call it accumulate or acute.

That's only in the cavity.

In my Hudson's Golden Gems, thisone, you know, you can't really

see it, but I'll hold it up, itborders on abrupt, almost steep.

Whereas this one, very gently shallow.

(39:44):

If you have ten of them, youcan write, you know, mostly

mostly obtuse, sometimes abrupt.

That's what the writers say.

You know, when you get home, pull outBussey, or if you have any books on

apple descriptions, and read them,and you're going to see how vague

a lot of them are about this stuff.

But some apples, here's one over onthe right, Belle de Boskoop, European

(40:08):

cooking apple, it is really abrupt.

You know, it just dive bombsinto the basin, whereas pardon

my French, I'll just say Damelotit is very gentle and so obtuse.

So the basin rim will have alwaysdifferent features that are describable.

(40:30):

When it is very smooth to the touchand the look, all the way around

the perimeter, We call it regular.

With my Hudson's GoldenGems, these are not regular.

So, and we're going toget to what they are.

If the rim of the basin is sort of gentlyrolling, like the rolling hills of, you

(40:52):

know, wherever, then we call it wavy.

And if it is pronouncedly sortof bumpy, we call it furrowed.

And furrowed apples usually havesome ribbing that goes down the

sides of them, but not always.

And so, my Hudson's Golden Gemis either wavy or furrowed.

(41:17):

I would even say, if you said it wasfurrowed, I wouldn't quibble with you.

It, it can be furrowed.

Now I didn't do a picture ofit, but, but Red Delicious,

what we call that is crowned.

So crowned, Red Delicious is a heavilyfurrowed apple that, and those five

bumps on Red Delicious, that is a crown.

(41:40):

Blanc, if you know that one,very, you know, super famous.

That one is definitely.

furrowed.

And Yellow Bellfloweris also very furrowed.

Now if you looked at one YellowBellflower, I might be able to fool

you because I could pick through mybushel and give you one that was not.

(42:02):

But if you look at 20 of them, Ican't fool you, and you'll look at

them and you'll see they're furrowed.

The apples can also be wrinkled andwhat wrinkled mean it's like it's like

being furrowed but right up tight.

against the calyx.

In this case, Dabinett is wrinkled.

You can see it's kind of hard, you know,it's hard because we can't feel them.

(42:24):

But the perimeter of the basin actuallyfrom this photo looks fairly smooth.

But if you look up tight againstthe calyx, it's definitely wrinkled.

And so we call that wrinkle.

Other apples like here's a NewTown Pippin have both They're

wrinkled and they're furrowed.

And many times if an apple isfurrowed, it's also wrinkled.

(42:49):

Okay.

Now you're going tocut one of your apples.

From stem to stern.

And, what you're going to try reallyhard to do, because if you don't,

it's not, it's, you might as wellthrow the apple away, is you're

going to try to cut exactly throughthe center of the cavity and exactly

through the center of the calyx.

And you can sort of pivot a little bitin midstream if you're missing, but you

(43:14):

really want to try your best to do that.

to get through both.

And once you get good at it, you shouldbe able to just slice, and I'm, and I, I'm

not kidding, right up through the stem.

But don't worry about that.

Okie dokie.

So now we've got our apple in front of us.

Remember, this is right side up.

This is just sort of a general look atwhat we're looking at on this slide, but

(43:37):

we're going to go through all these parts.

So the first thing that we have iswe have what's called the calyx tube.

So the calyx tube starts at the calyx andgoes in towards the center of the apple.

And if the calyx is open, now youknow what an open calyx is you

went, , right through that big opening.

The calyx tube some writers say it canonly be two things, conical or funnel

(44:00):

shaped, but it can also be urn shaped.

And an urn shaped funnelis just an inverted cone.

It's like a subset , ofa conical calyx tube.

Now, I don't know how good your eyesare, but here's one of my Hudson's

Golden Gems, and it has a really longconical calyx tube that goes almost all

(44:27):

the way up into the center of the apple.

Another one of my apples, this isa different apple I just cut up.

This also has a conic tube,but it's much shorter.

This is another reason why if you'rewriting a description that you're

going to put in your catalog or.

You know, your little bookyou make for yourself, or, you

(44:48):

know, for a much bigger purpose.

You don't want to cut one openand then describe the calyx tube.

You want to cut open three orfour and then say, oh, okay, you

know, that one that was reallylong and conic is an anomaly.

They tend to be shorter.

With conic tubes, some are quitesmall and very, and very flat conic.

(45:13):

And you know, sort of more likethis, and then others very narrow

and, and long, or narrow and short.

It's a worthwhile descriptor to doas you're describing your apple.

Okay, so a funnel shapedtube looks like a funnel.

It's got that inverted trianglepart, and then it has a cylinder.

(45:36):

And does anyone have a funnel shaped tube?

Okay.

Oh, okay.

So, awesome.

Okay, so this one, that one that I showedyou at first, is almost funnel shaped.

It's more like elongated conic.

Does anybody have a short conic tube?

Okay.

So my guess is that with Hudson's GoldenGem, That in general, it's a conic

(46:02):

calyx tube, but going to be riskyto say that they're always like that.

In the calyx tube are the stamens, andthe stamens are these little tiny hairs.

The stamens can be, can be marginal,which means that they're out

towards the opening of the calyx.

(46:23):

They can be median, which means they'resort of halfway up the calyx tube, and

if they're basal, it means that they'reway in towards the center of the apple.

And with Robert Hogg, the Britishpomologist, he was really into

stamen location, often the codlingmoth, the first thing they do is

(46:44):

destroy the calyx and then they wreckwhere, the location of the stamen.

So if you live in the world of codlingmoth and you're trying to describe

apples, what I do is, where we have alot of them, I'm always looking for.

The apples , where thecalyx is still intact.

You also can't tell if the calyxis open or not if it's been

(47:07):

attacked by a codling moth.

One thing I've begun to work on is how dowe define a small, medium, or large core?

And all the pomological writers, theyjust say it's small, medium, or large.

They give no criteria at all toFor how you're going to define it.

(47:27):

The vascular tubes, which are thoseten little dots, you can say the

core begins there, or you can say thecore begins in where the opening is.

We'll get to the opening in a,in a, probably a slide or two.

So what I've been doing isgoing into mostly using S.

A.

Beach, Apples of New York, gettinghim to declare what's a large core.

(47:51):

So I found some, includingYellow Bellflower.

And then I take my apples of YellowBellflower, measure the diameter,

measure the diameter of the core,and then , come up with a proportion.

So that once we do this for about maybeten apples each, classic historic apples

(48:13):

that the writers called me small, medium,or large cores, Maybe we can come up with

a proportion to the diameter of the apple.

Because it can't be the size of thecore, because you take an apple like,

many of you know, Wickson or Dolgo,even if the core took up the whole

apple, it'd still be a small core.

And, and that's not whatwe're talking about.

(48:34):

We're talking about the proportion ofthe ratio of the size of the core to

the ratio, to the size of the apple.

Get out your knife and cut, cut acrossthe equator of cut it across the middle,

not towards the apex or the or the base.

You can also, in a pinch, you couldjust put together your two sides

(48:56):

and then cut it across that way too.

Here's our apple cut inhalf across the equator.

And you can see those little Sothose little dots, those ten dots,

those are the vascular tubes.

And some people can, you would say thatwould be the definition of the core,

but either way it's all going to beproportionate to the size of the apple.

(49:20):

And you can see, although it'shard to see my writing down there.

I wrote the percentageof the ratio for both.

But I would say that my Hudson'sGolden Gem is sort of a medium,

I'd call it a medium size.

It's not huge, it's not tiny.

Some apples the core isreally big, noticeably.

(49:42):

Especially once you start, you know,you start looking at lots of them.

Or it's really small.

And some, back when there was sortof a real applesauce industry, before

they just took, you know, essentiallyjunk culls , from the packing houses,

but they grew applesauce apples, thenthe small core was highly prized.

(50:02):

So there are reasons.

And then many of the classic cidertexts, very old, will talk about the

value of a large core, because they'llsay that more of the good stuff is in

the skin and the core, not in the flesh.

Now we're going to hop back to, theone we cut the other way and the core

(50:23):

can be close to the stem or close tothe calyx or centered in the middle.

If anything, you know, I'm onlylooking at, well I can look at

two if anything I'd say my core isreally up towards the stem a bit.

Are people seeing that or, orare you disagreeing with me?

Okay.

(50:43):

So, if I was going to make a pronouncementabout Hudson's Golden Gem, we would

say it was sessile, meaning that itis closer to the cavity or the stem.

Now we have the hidden star, , thepentangle, the five pointed star,

and we want to know whether itis axile or Abaxile And I'm going

(51:10):

to cut up another one of mine.

There's an apple cider company,I'm not sure where they are,

that, that's called Hidden Star.

Does anybody know that one?

I don't know where they are,back east somewhere or something.

And their, their label lookslike that apple over on the left.

That's like the perfect,axile, closed core.

(51:34):

This is the perfect abaxile core.

My Hudson's Golden Gem, it's where thoseseat cells do not extend to the center of

the core, but they stop, and you get a bigsort of empty, empty space in the center.

Here's another one of myHudson's Golden Gems I just cut

(51:57):

apart, and it's almost axile.

It's still sort of, this one, I wouldsay, is incompletely pollinated.

Because some of the cellslook a little weird.

I don't think this was fully pollinated.

I'm going to cut open anotherone just to see what we get.

What are people getting?

Are you getting axile or abaxile?

(52:17):

Axile.

Abaxile?

Okay, here's another one.

This one is almost axile.

And for some cultivars, it isreally a defining characteristic.

So it's, it is definitely, eventhough it can be variable, another

reason why you want to have a bunchof apples in front of you, in many

cases, it's not that variable.

(52:39):

So going back to, to thisapple, we have the core lines.

The core lines are, these very lightlines that surround the core and

then, either meet at the inner endof the calyx tube or they touch up

(53:00):

against the side of the calyx tube.

When they meet one another in sortof a, you know, a junction, then

we say the core lines are meeting.

Okay.

And when they touch the side of thecalyx tube, whether it's conic or funnel

shaped, then we say they are clasping.

(53:21):

When the calyx tube is funnel shaped,like 99 percent of them will be clasping.

When it's conic, some may beclasping and some may not.

But it is often a defining characteristic.

now we have the carpels.

The carpels are the seed cells.

And they are really hard todifferentiate between each other.

(53:46):

Some, and this is another placewhere the historic writers, Come up

with all sorts of names for them.

Roundish, chordate, oblong we have ovate.

We have roundish, ovate, elliptical,obchordate, and so forth.

What I think is important foryou , is not to try to memorize these.

(54:08):

You should definitely know a cavityand a basin, and abaxile and axile.

But you should just knowthat these Can be important.

And the carpels can be aemarginate or mucronate.

And they're also really hard tosee because you've got to cut

right through the perfect part ofthe seed cell to even see this.

(54:28):

And in a emarginate, they point backtowards the center of the apple.

And when they're mucronate,they point away like an almond.

Also pretty interesting, especiallywith the apple that we have, you know,

And this is definitely an importantcharacteristic, and this is one that

can be a defining characteristic,is the seed cell smooth or tufted?

(54:52):

When the seed cell is tufted, It haslittle wispy, sort of cottony looking

rings or little, little things thatlook like scales on a fish, and

when it's smooth, they have none.

And so do you havetufted carpos or smooth?

(55:15):

Tufted.

Tufted, yeah.

And this is a great example ofa tufted, of tufted seed cells.

I don't know what the split is, if it's,half the cultivars have it and half don't.

But there is a significant number of both.

So here's northwestern greening.

The reason why there's only halfor a quarter of the apple there

(55:35):

is I had to cut it about eighttimes to get through the carpel.

But that is definitely a smooth carpel.

There's no tuftedness in it.

If you know woolly aphids, I thinkof it as looking like there's woolly

aphids inside the core of your apple.

which they never would be.

Now we get to the raison d'etre.

(55:55):

I picked some, some royaltyhere to talk about the flavor.

Up at the top, we have royal sweet,which is a historic main apple very rare.

And when you see the word sweetin the name of a historic apple

in North America, it is always.

(56:17):

low in acidity.

Tolman Sweet, Pound Sweet,Pumpkin Sweet, Ramsdell Sweet.

These are all low acid apples, and theywere all used for very specific purposes.

Animal food, certain kinds of cooking.

They cook in stews really wellbecause they hold their shape.

(56:40):

They're like turnips orpotatoes in your stew.

They were also used to make molasses.

So you can press them.

You have an insipid cider with no acidity.

And then boil it down likeyou would maple syrup.

And then you can get a shelf stablemolasses that is indistinguishable

from sugarcane molasses.

(57:02):

And you can keep it for years.

They make horrible pies.

And they do not cook well in applesauce.

Though if you cook them forever, theyYou can finally make them into sauce.

On the right, we have King David whichsort of mid Atlantic to Southern, I

guess it's Arkansas apple that was growntraditionally in Northern New England and

(57:24):

grows really well and has great acidic,or sometimes we say subacid flavor.

Then we have Kingston black, the classicbitter sharp, and Royal Jersey, a classic.

bittersweet, which is also aswith the historic sweet apples.

Very low in acidity when you'reusing us to do apple identifications.

(57:48):

This is really helpful because ifyou're out in the field or in an old

orchard and you take a taste and it'sa sweet apple, you've just eliminated

about 80 percent of the possibilitiesof what the cultivar might be.

Because the sweet apples are a verysmall subset of the, especially the

(58:08):

historic, well, even more of themodern ones, there's essentially none.

Except, you know, a modern cider cultivar.

The apples nowadays, unfortunately,the word sweet has been co opted.

So you get apples like sweettango, sweet sixteen, etc.

Those are not sweet apples.

(58:29):

Not in their true sense, historically.

The last and the most important questionfor me is what is it about this apple that

I can describe it and I won't forget it?

So, if I look at my Hudson's GoldenGem and on my key form, which is

(58:51):

what you're looking at, down at thebottom, I would write here, I'd

write something like, well, it's, Youknow, partly to mostly recited, it's

roundish ovate, it has a fairly longstem, it tastes How does it taste?

Is anybody trying it?

Maybe we better taste it.

What is it?

Is it a bittersweet?

No.

(59:11):

Is it a sweet?

What is it?

Does it taste like a pear?

In Maine, they taste like a pear.

So what I do, and I say in 20 words,but it could be 40 words, whatever, is

write your general impression of this.

Because what you don't want to do is goback to the form and go, Oh, what was that

(59:35):

abaxile apple that I found the other day?

What you want to do is you wantto look at the bottom and go, Oh

yeah, it's that elongated conicrusset apple with the long stem.

And then it's really handy also you go andlook at your form and Scrap of paper or

(59:55):

whatever, and said, Oh yeah, it's Abaxile,, that's all helpful, but having that

overall impression is really valuable too.

So for more information, I have a bookyou can get it from our website, which

is called Out in the Limb Apples,and sometimes you can from some

(01:00:16):

bookstore, but we're not on Amazon.

Thank you very much.

And with that, I leave you here.

This is Ria Windcallersigning off for now.

Looking forward toseeing you in Ciderville.

Orchards, there is a reasonwhy we do it like this.

(01:00:39):

Yeehaw!

Popular Podcasts

Dateline NBC

Current and classic episodes, featuring compelling true-crime mysteries, powerful documentaries and in-depth investigations. Follow now to get the latest episodes of Dateline NBC completely free, or subscribe to Dateline Premium for ad-free listening and exclusive bonus content: DatelinePremium.com

24/7 News: The Latest

The latest news in 4 minutes updated every hour, every day.

Therapy Gecko

An unlicensed lizard psychologist travels the universe talking to strangers about absolutely nothing. TO CALL THE GECKO: follow me on https://www.twitch.tv/lyleforever to get a notification for when I am taking calls. I am usually live Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays but lately a lot of other times too. I am a gecko.