Meet Pascale Sablan, a visionary architect with an impressive track record of transforming the built environment. Pascale has been recognized as one of the most influential architects of her generation, with a practice characterized by a commitment to excellence, innovation, and sustainability. She currently serves as the NOMA Global President and Chief Executive Officer at Adjaye Associates, New York Studio in charge of all operations, whilst continuing to lead efforts for architectural projects, community engagement and business development.

Pascale is not only an accomplished architect but an activist dedicated to addressing disparities in her field. She founded Beyond the Built Environment, empowering women and BIPOC designers. As the Global President of the National Organization of Minority Architects, she's a trailblazer, being the fifth woman to hold this position in the organization's 52-year legacy.

Pascale's advocacy has earned prestigious accolades, including the Architectural League 2021 Emerging Voices award and the 2021 AIA Whitney M. Young Jr. Award. Inducted into the AIA College of Fellows, she's the youngest African American to receive this honor in its 167-year history. Pascale has received grants from the Graham Foundation and the Architects Foundation for her research and exhibitions.

Her influence extends globally, with lectures at esteemed institutions like RIBA, the United Nations, and the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Described as a "powerhouse woman" in the media, her work has been featured in The New York Times, NPR, and Forbes, and she was recognized by Oprah's Future Rising platform. With a Bachelor of Architecture from Pratt Institute and a Master of Science from Columbia University, Pascale Sablan, with her unique perspective, unwavering dedication, and undeniable talent, is set to shape the future of architecture for years to come.

TOPICS DISCUSSED IN "OWNING YOUR OWN NARRATIVE":

- What is Pascale's earliest memory of being creative?

- The lengthy educational journey to becoming an architect

- 5% of Black students go into architecture school and only 3% graduate. 7 HBUs creative 65% of the students.

- What happened in Pascale's history of Architecture class and how it cemented her purpose as an advocate

- The responsibility of showing up as you are in spaces where you don't look like everyone else

- Architect Magazine's Erasure of Justin Garrett Moore

- Google and it's definition of great architects

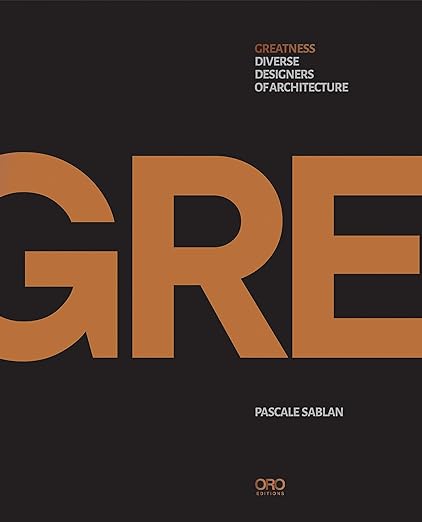

- Pascale Sablan's new book set for release in September

- How activism isn't all always about action, it's about wholeness

LINKS:

https://pascalesablan.com/

https://www.adjaye.com/

https://www.beyondthebuilt.com/say-it-loud

Episode Transcript

Pascale Sablon knew from a young age that she wanted to be an architect.

One of only two Black women in herHistory of Architecture class, it was

early days in her freshman year to Whenthe professor called on her to stand.

Pascale (00:22):

So there's a level of geeky excitement that was on my face that

I just want you all to envision.

But in one of our architecturehistory classes, the professor asked

me and another student to stand andsaid, okay, these two will never

become architects because they'reBlack and because they're women.

Kim (00:36):

That moment shook Sablon, but it also cemented her purpose.

Now, as CEO of visionary architect SirDavid Adjaye's New York office, Sablon.

And president of the NationalOrganization of Minority Architects,

Sablon is dedicated to helping womenand people of color not only challenge

(00:57):

a broken system, but dismantle it.

Pascale (01:02):

Hi, I'm Pascale Sablon, and this is a lesson

on owning your own narrative.

Kim (01:19):

So tell me, what is your earliest memory of being creative?

Pascale (01:24):

Ooh.

Wow, what a great question.

My earliest memory of being creativeis my mom always had collected these

incredible interior design magazines.

And I would take her shoe boxes, dumpout the shoes, and I would staple

and pin and couple together a fewboxes to make like a floor plan.

Kim (01:43):

And then

Pascale (01:44):

I would take index cards and create like little door swings and I

would Orient them into inside the boxand then tape some of the pictures from

the interior design magazines that kindof laid out some designs of subspaces.

But I remember that was likea lost, like early childlike

memory of just being playful andplaying with space and design.

(02:04):

But in general, I was always an artist.

I was always drawing something,illustrating something, always

loved art and creativity.

And that actually was fun becauseI used to be a little ballerina.

And my brother Jeffreywas taking art classes.

And I think one day the balletclass got canceled or something.

So I just went with Jeff to his artclass and she was like, sure, she

(02:25):

can come for the course session.

No big deal.

And I was like, thisis what you get to do.

And I was like, mom, I don't wantto do ballerina stuff anymore.

I want to go to art class.

And she's like, I've investedso much in your tutus and feet.

Years of ballet classes andgave it all up with Jeff.

(02:47):

I guess those are some of my earlyfun memories as it relates to art

and design and being creative.

Kim (02:52):

I

Pascale (02:52):

love that.

Was she, she a designer?

No, my mom's an accountant.

Kim (02:58):

An accountant with a hidden, probably a hidden visual sense in there.

She's got two kids whoare artists for sure.

Okay.

I love that.

Yes.

So.

You're being creative when you'reyounger, what makes you decide

you're going to be an architect?

Pascale (03:15):

I was a camp counselor at the Pomonok Camp Center in Queens and

really had fun with the art program thatthey had there and would always help

my little ones that I was overseeingwith their projects and just like

creativity and even made their costumesfor the The play, if you could find

that picture somewhere, hilarious.

(03:35):

But anyway, some, somebody might'vebeen dressed up as a gigantic Sebastian

and made a whole bunch of littlemermaids dancing, but the art teacher

and one of the camp directors justnoticed my love for art and gave

me a whole wall to draw a mural.

Oh, that's incredible.

And so I'm 11, 12years old, like 11, 12.

And I decided to do with thisjungle gym with this multicultural

(03:57):

community as like my piece.

And I was drawing the junglegym and somebody walks by

and goes, wow, you could drawstraight lines without a ruler.

That's a great skill foran architect to have.

And this individual was literallyhaving this out loud thought, but

it was just like, Oh, I alwaysthought about art as a hobby.

That was separate to whatmy career would need to be.

(04:20):

And so in that moment, it occurredto me that I could do both, right?

I can merge them and itcould be one and the same.

And I.

I truly love this concept of drawingsomething or having something

in my mind and having it createinto a space where people have

to impact and engage with it.

And so since I was 11, 12years old, I knew that I was

(04:41):

going to be an architect.

That was my answer.

Whenever somebody said, what areyou going to be when you grow up?

So nobody is surprised.

That is what I ultimatelychose to do as a career path.

Kim (04:52):

And it takes a long time to become an architect.

I don't think people realizequite how long it takes.

It's pretty much the equivalentof becoming a doctor in

many respects, right?

Can you talk about youreducation path to that?

Pascale (05:08):

Sure.

So I definitely did an interesting pathand I'll share the nuances as it goes.

And then also hold the caveatthat things have absolutely

changed since I went throughthat process way back in the day.

Okay.

But it began with a bachelor's degreein architecture, and that's a B Arch.

And that's actually a veryrare degree to obtain.

Not many schools actually offer thatbecause it's a five year bachelor's

(05:29):

degree and it's an accredited degree.

So that means once youcomplete that better degree.

and you complete your internship, youwould be able to sit and take the exams.

Most schools offer a master'sin architecture, which is an M.

Arch.

For me, after I finished my B.

Arch, my mom required meto get a master's degree.

Can I just ask

Kim (05:50):

you about that for a minute?

Why did she require you?

What was that about?

Pascale (05:54):

Sure.

My mom said a few things.

The first was, When you firstgraduate, you're young, you're cheap,

and you're easier to get a job.

But once you're in an industry,it's very easy for you to get

surpassed by other people in terms ofpromotions and a level of authority.

And to be quite honest, the demographicsof the profession, she wanted to make

(06:14):

sure that I had all my paperwork inplace so that nobody can question my

ability or my capabilities to be there.

And then lastly, she said thatmy family would be in a position

to support like me staying inschool just a little bit longer to

Kim (06:26):

complete

Pascale (06:26):

that degree.

So I graduated from Pratt in thespring of 06 and a week later started

my master's program at Columbiaand then graduated in the spring

of 07 with my master's degree.

So I say all that to say, so thattook me a five plus one, which

is six years to get the degree.

But again, most people do a four yearbachelor's degree in something else.

(06:48):

And then a three year master's programat MR to make it a total of seven.

So that takes a little bit more time.

Then we have something at thetime was called IDP for me,

which was the internship process.

Now I believe it's called AXP, whereyou ultimately have to do about three

years plus or minus of internships.

But that years is really.

(07:08):

Connected to different phases of aproject, and you have a supervisor who's

saying that you're getting the kind oftraining you need to accomplish that.

Then, you take your exam.

Exams, right.

So, during my time, if youtook an exam, it took six weeks

before you received the result.

And then if you did not pass, you hadto wait six months before you could

(07:29):

take that chapter or that section again.

So, it took me 14 tests out of the sevenbefore I passed all that I was required.

And there was also something calleda rolling clock, which means once

you passed your test, you had fiveyears to pass all of the other

tests or they start to expire.

So that was anotherkind of pressure point.

(07:50):

I bring that up because through thecollaboration of Noma and NCARB, we

were able to do a survey baseline onbelonging and identified some of the key

kind of things that were challenging.

Our membership in terms of gettinglicensure and part of it was having

their exams expire And so I believelast year if not the year prior so

forgive me and carb but shout outsto you They expired or removed that

(08:12):

requirement as it relates to itSo people are able to continue to

take the exams and pass accordingly

Kim (08:17):

And noma is the national organization of minority architects.

What's n carb?

Pascale (08:23):

So n carb stands for the national council of architectural

registration boards And theyoversee the legal constitutions

as, as it relates to become aregistered architect in the country.

And so they really lead the effortsin terms of taking exams and,

and the requirements and makingsure that you fulfill all the

requirements of your jurisdiction.

Becoming an architect is one thatis quite lengthy from the time you,

(08:46):

let's say, graduate from high schoolto the time that you can consider

yourself a practicing architect.

I think, according toNCARB, it's 11 to 12 years.

And for me, it took me 13 years.

Just because of the strugglesthat I had with the exam process,

and I needed to wait the sixmonths, which also is another rule

that NCARB was able to remove.

Kim (09:05):

I wanted to bring up that, that story of just the length of education

for a number of reasons, because thereis that mentorship aspect in there.

There is, now fortunately your familywas able to support you financially

during the master's portion of that,but there is a lot of, I guess assumed

(09:28):

wealth in that time and also thefact of, you know, when you're being

mentored by somebody that you're goingto find somebody who is going to be

interested in you, invested in you,

Pascale (09:41):

in whom you can see yourself.

There is a privilege of studyingand becoming an architect.

And so some of the collaborationsbetween NOMA, which I am the

global president of right now.

and CARB and other anchor institutionsthat really control the profession.

We're identifying some of thosechallenges and finding ways to

remove the obstacles in a way thatdoesn't reduce the requirements

(10:03):

in any way, but makes it moreattainable for more people.

And even some of the projects, whenyou take the exams, there were certain

projects they needed to memorize whowould be architects, even making sure

that there was projects that were ofdiverse professionals within there

was also something quite important.

And so.

Even the study of what questions arebeing asked, NCARB has taken a really

great effort and initiative of makingsure the exam itself is equitable.

Kim (10:28):

Yeah, I thought it was interesting, 5 percent of black students go into

architecture, only 3 percent graduate.

And that is a powerful statistic.

And then you mentioned that 7HBCUs are the ones that are feeder

schools to architecture as well.

I've seen you, uh,

Pascale (10:45):

Talk about that.

Yeah, I think I got it from RobertEaster, who actually won the Whitney M.

Young Junior Award more recently,shared about the importance of HBCUs

in the pipeline of architectureand diversifying the profession.

And those seven HBCUs output, Ibelieve, 60 to 65 percent of African

American students who graduatewith a degree in architecture.

(11:06):

So when we were talking about how canwe make the most significant impact

in terms of creating diversity there,we were Part of that strategy was to

focus on some of those schools as well.

Whereas the rest is kind of likemy experience where we're one of

two or one of three in the entireschool of architecture that is

participating in that experience.

And that comes with its own challenges.

Kim (11:32):

You're in your first year at Pratt.

You are there for your B Archdegree, as we just discussed,

and you are asked to stand.

So tell me about that story.

Pascale (11:44):

Sure.

So since I shared that I've alwaysknown that I want to be an architect,

I was actually quite eager to startarchitecture school and part of the

reason why I wanted to go to a B.

Arch program is that I knewfirst year, first day, I would

jump into architecture project.

So there's a level of geekyexcitement that was on my face that

I just want you all to envision.

But in one of our architecturehistory classes, the professor asked

(12:07):

me and another student to stand andsaid, Okay, these two will never

become architects because they'reblack and because they're women.

And And I remember being very surprisedthat the professor made that statement,

and it wasn't being reprimanding inany way, it wasn't like we were being

disruptive in class, but it felt forhim like it was pure facts based off

of what he had experienced, right?

(12:28):

I also was also taking stockof the large classroom and all

the students in there, and thatactually there was only me.

And one other person who fitthat criteria and also the

silence of my peers, right?

Like it didn't impact them.

They didn't seem to be outraged by it.

And so it surprised me and it shook me.

And I sat down and the person to myleft, I'll never forget him, Simon C.

(12:52):

He turned to me and said, you better notlet that be the reason that stops you.

Prove him wrong.

He used way more colorfulwords, but that's what he said.

And as a very competitive person, thatwas the sentence I needed to hear.

But I often talk about that momentbecause it was so You have to understand

I grew up in Queens in an area calledCambria Heights, which was like 99

(13:13):

percent black, 97 percent Haitian.

I then went to an all girlsCatholic preparatory high school.

Me too!

Um, the Mary Lewis Academy.

And so I was always taught howgreat I am and how amazing I

am because of these things.

And so to kind of come into a spaceand so that I'm inadequate because

(13:34):

of them was just very jarring.

And it also made me take stock thatI am a rare representative and so

therefore the responsibility ofwhat it means when I show up into

a space that I'm not just showingup as Pascal, but I'm representing

my gender, my race, and what doesthat mean if I have a stomach ache?

It's not Oh, no, Ican't miss that class.

I can't be like black girlsdon't go to class, right?

(13:55):

So I had to really be mindfulof what my performance meant.

And I wanted it to always be thecatalyst for more opportunities

rather than limiting them.

I mean,

Kim (14:07):

when I, I was watching a video presentation of you tell

that story, and I, It was like, I,I mean, I freaked, I gasped, and

then I had to calm myself down.

I don't want to spendtime on that person.

But were they fired?

Were they reprimanded?

Did they just get away with

Pascale (14:26):

that?

At the time, it didn't evenoccur to me to report it, right?

It just was like somethingthat I just understood to be

like the new reality of things.

And I also identified that momentas a moment of privilege, because

it was, the reason I can speak to itis because it was the one and only

instance I ever had to deal with it.

No other teachers, no otherclass, even in his class, that

(14:47):

he ever bring it up again.

I will

Kim (14:50):

say though, it's interesting when you give this presentation,

you say that you ask people,have they ever experienced it?

And there's always somebodyin the audience who's, and I

had an experience similar aswell, very similar in that way.

And I feel like this is how,who gives people the right

to make these decisions.

Pascale (15:07):

What I recognized from him was his lived experience

of what he had understood.

And that's why some of mypurpose was developed around.

Elevating the work and identity of womenand people of color, because when you

think about the professionals and thegreat architects were told to learn

from and to learn are all white male.

So it also revealed a very big gap.

(15:27):

And so I knew at that point, I couldn'tjust come into the profession and

be an architect, but I had to alsochange the profession as well and

create part of my advocacy arm of whoI am and how I present in the space.

And to your point, wheneverI do share that story, I do

ask the audience to stand.

So that people could see how verycommon, it's one thing to see me

(15:48):

who you don't know on stage say it,and then it's another to kind of see

your co worker stand up, and yourboss stand up, or your daughter stand

up, and it becomes a conversation.

Kim (15:56):

It's like Me Too, it's very much like Me Too, that

men could not believe, right?

Pascale (16:01):

We're starting to get at those kind of processes, like what

is the process when injustices occur?

What's the position of accountabilitythat we're able to address?

And just really leveraging what we'rehearing from our members, from our

students to understand what are someof the challenges that they're facing,

and be able to address that andcreate systematic changes that then

removes more obstacles and createsa more equitable and pleasant path

(16:23):

to architecture in the profession.

Architecture Camps from Fornoma, it'sa global initiative that we have.

And these kids are so excited tolearn about architecture and design

something and present to their parents.

(16:43):

And they're skipping out the door going,saying, I'm going to be an architect.

And what happens when they try tofurther that research and go further?

What happens when they Googlethe words, great architects?

And so I ran that search and Googlecomes up with a banner, like an

image banner of just names and faces.

I went through the first50 and at the time.

(17:05):

Only one was a woman, Zaha Hadid.

I was gonna say, I betyou it was Zaha Hadid.

Zaha Hadid and Zerowere African American.

And I'm looking at this list andsome of the names on this list

is Michelangelo and Raphael.

And saying that no woman, only onewoman has had significant impact

and no black person, absolutely not.

(17:26):

That's flawed.

The very audacious Pascal wentto the Google headquarters

and met with their BGM group.

And walk them through what I wasseeing and trying to understand why.

And they said, Pascal, there'sliterally not enough content out

there that lists you all as great.

And simultaneously, I had beencurating and hosting a series of

exhibitions called Say It Loud.

(17:47):

These Say It Loud exhibitionselevate women and people

of color of that location.

So it's the travelingactivation, I like to call it.

And we have posted 47 exhibitionssince we started in 2017.

And we have elevated thework and identity of 1, 112

diverse designers globally.

Inspired by that response fromGoogle, I then created the

(18:08):

Great Diverse Designers Library.

And the title link being great is onpurpose because the SEO didn't have

enough information to call it great.

Everybody's bio was updatedto say the great architect.

The great urban planner, the greatlandscape designer, the great interior

designer to challenge and create aspace where we are being elevated.

And when you look at the work,you're like, Oh my goodness,

(18:30):

this is extraordinary.

This is great.

And to get a level of comfort ofbeing told you are great, because

we are very much challenged byhearing that and shy by that and

actually step away from that.

But at the same time, donot hesitate to digest that.

Other main messages.

Kim (18:47):

That's right, because those messages are pervasive, but just the

idea of who controls the conversation,who controls the conversation.

I and I do want to move into alittle bit of that because you do

speak to it's the pride, but it'salso how to deal with the media,

how to tell your story in the media,getting comfortable telling your

(19:08):

story in the media and the media.

One of the examples you brought upwas the erasure of Justin Garrett

Moore in an article and then a videopresentation for Architect Magazine,

and I was, again, in complete shock.

Who decided that was a good idea?

But if you want to, couldyou tell us that story?

Pascale (19:30):

Sure.

So, during the AIA conference, whenit was in New York, they had a panel.

AIA and Architects Magazine had apanel in their expo that had Different

architects and designers and planners.

And Justin Garrett Moore, I think waspart of the center of kind of creating

that panel and had a beautiful voice.

And it was about fivedesigners on the stage there.

Shortly after the, uh, videoof the, the lecture was then

(19:54):

posted on the official website.

And in that video, JustinGarrett Moore, who was sit seated

center stage, and he's the only

Kim (20:02):

black architect.

He's the only

Pascale (20:03):

black architect and planner, recently elevated to fellow of

a PA, so I'm very proud of him.

Was completely edited out of the video.

And so that means any mention of him,introduction of him, any responses

of any of these questions, thecamera angles in which they use, and

the only time you catch him is hisshadow silhouette when they zoomed

into one of the other speakers.

(20:24):

And what was powerful is that hereached out and said, what's going on?

Why did this occur?

And he received very limited feedback.

And then 2020 occurred in George?

Yeah.

And George Floyd.

And then they put out an article.

That basically implies anaccidental erasure of Justin.

That

Kim (20:42):

is not an accident.

And then, so to me, Oh my god, yeah.

So

Pascale (20:45):

to me, it's like, you know what, I can't photoshop a curl

that doesn't take a few minutes,let alone editing out a whole

person's existence from a panel.

And so, I was saying to people that it'snot just being intentional about Framing

our narrative and making sure that we'rein places and speaking to our projects

and our, and our, what we're working on,but also fighting the force of erasure.

(21:07):

That there's an actual force of thosewho are editing us out of the spaces

and the credit that we are often due.

When Steve Lewis always says,who will tell our story?

And my answer is us.

We have to tell our own story.

We need to document.

So when you finish a project,don't just sit and hope that

Architizer or Architect Magazineor whomever is going to pick it up.

You make a PDF, you make a document,you send it over, you push, you

(21:30):

push yourself out there and allowus, or people like myself, who

are very happy to elevate you tocontinue to do that with all of our

energy and all of our resources.

We need to

Kim (21:42):

prove that we exist.

We exist.

There's a reason now that we aretelling those stories and that we

should have been telling them Florida.

Yeah.

I think there's a reason thatwe know them now is because

we have started to tell them.

Because we are believingthat we're valuable.

And I think women in particular strugglewith this notion of Are we valuable?

(22:08):

Is our work valuable?

Is it valuable enoughcomparatively to men?

Pascale (22:13):

So I, I appreciate that.

I appreciate that Allie, youand I'm going to take it.

Yeah.

I keep thinking about all thisrich content that I received or all

these exhibitions and I love thewebsite and I'm so proud of it and

really proud of the support that Igot from the Sarah Little Turnbull

to actually turn the designerslibrary into a sociable engine.

But I also think about like, how can IContinue to think about that experience.

(22:37):

And so I'm publishing a book, andthe book is called Greatness, Diverse

Designers of Architecture, andit's divided into four typologies,

and it's focusing on how eachtypology has been used to harm in

the past, and how architecture anddesign and planning can heal, and

then curate 10 amazing projects.

Um, and it's from our librarythat is of that typology and

(23:00):

addresses some of those concerns.

Kim (23:01):

Can you give me an example of one that you love?

Pascale (23:04):

Sure.

I have to be carefulbecause nothing's out there.

Right.

Keeping that in mind.

Kim (23:08):

Yeah.

Pascale (23:09):

We featured projects that have great community engagement processes.

So maybe sometimes it's not justnecessarily the end result or the

product itself, but also the processin which we were able to receive

or end at the design strategy.

It's a global publication andit's leveraging the same kind of

language that we talked about.

And I remember when I wasnegotiating different book deals

with different publishers totry to make it come to fruition.

(23:31):

Some publishers werelike, nobody's gonna care.

We don't need a book about this.

And the last book that I could comeacross that was featuring people

of color was Jack Travis's bookthat he published in the 1990s.

And so the idea of having morebooks that just celebrate our work

and who we are was something thatI became very passionate about.

And another publisher said to me, Idon't want any white women in your book.

Kim (23:54):

Hmm.

Pascale (23:55):

That there's enough books about white women's contributions,

but We actually don't have anythat's focused on people of color.

And I said, I hear you, but mymission is to elevate the work

of women and people of color.

Because when that professorasked me to stand, he didn't

say stand because you're Black.

He said stand because you'reBlack and because you're a woman.

And although the issues that womenface are different from those

(24:18):

that are people of color, theyare yielding very similar results.

We're not getting paid the same,we're not getting promoted the same.

And so this is somethingcritical that we need to address.

So I would not move off of my missionand ultimately that killed that deal.

But I, and it's fine that it prolongedcreating this book that I think is

(24:39):

powerful and important and necessary.

And it's set to release this yearin October as I step down as the

presidency, I'm going to releaseit in at the NOMA conference.

And so that's why I'm saying topeople, you don't have to wait till

a publisher comes to you or whomever,you can put yourself out there and

start to document your own story,because then it's content that

then it's content you pull from.

(24:59):

And just that act of being a historianof your own story is important.

You don't have to wait forsomeone else to describe you.

And that's why I like to say itloud, exhibitions with the library,

it's a self submitting process.

You tell your story, you select whatheadshot, you say which project, you

talk about your contributions and thisis the first step of empowering your

(25:20):

voice and your importance in our entireenvironment, in our entire world.

It also helped me develop anotherinitiative called Say It With

Media, which is asking publications,both digital, print, and broadcast

to keep track and document.

How many women and people ofcolor they're featuring in their

content and increasing it to 15%with a 5% increments every year.

Kim (25:44):

And you're talking about shelter publications as well, like the eighties

and the daisies and the all of that.

The world.

Yeah, all of it, yeah.

Pascale (25:52):

But then I also ask them to use their resources to also

unearth history and importantinformation about us as well, because.

They have an ability to get informationthat we don't and I was getting so

frustrated that social media waswhere I was learning so many critical

facts about important figures andI'm like, why did it take this

(26:15):

Instagram post for me to understand?

That this person existedand that is what they did.

I will

Kim (26:20):

say too, though, that, again, to that first point about owning your

narrative, there's so many people who donot think their narrative is important.

Correct.

And that it remains hidden untilgreat granddaughter comes along,

or grandson, or whoever it is, andsays, you know what, my mom, or my

grandmom, or my aunt did X or Y.

(26:40):

And that's why we are getting this.

At en masse right now because there'sso many young and I think about

young black women in particularwho are Rocking it Right who are

out there with their platformsmoving the narrative in the needle.

And so I I again I do think it'simportant to To understand the

(27:02):

value of your own story And how enmasse the collective The Unified

Collective of those stories tips theneedle on what we pay attention to.

Pascale (27:15):

That and putting this book together and I'm

so proud of the content.

You all are going to be like, wow.

Like, I know this, but I alsodon't want it to just be an

architecture community book.

I want it to be a book that anyone who'simpacted by their built environment

picks this up and goes, Oh, wow.

I didn't understand that was partof the planning and how highways

(27:36):

cutting into my neighborhood actually.

Disrupted and demolished a lot ofthriving communities, like just

understanding how architecture canand was used to harm and how it

also has been really a beautifulhero for a lot of communities.

So how do we leveragethat and understand that?

So I really want to make sure thatwe stop, let's say, talking to just

ourselves all the time and havingimportant conversations with other

(28:00):

individuals to understand how canwe move that kind of that progress

forward and disseminate the workloadthat is not the work of a few.

But it's the requirements of everyone,and I know that's a very controversial

thing to say, but that's why Idon't consider myself an activist,

which is about sharing informationand getting people activated to get

people aware and get people motivated,but more of an advocate who's happy

(28:23):

to sit year in, year out, refiningpolicies and procedures that hit and

address community needs and issues.

And then putting it in a way whereno matter who's at the table, it's

something that they have to follow.

And for me, I'm down for the long game.

I'm patient.

I ain't going nowhere.

We're going to make this

Kim (28:41):

happen.

We'll add that there's somethingabout two in this moment.

Just allowing yourself to be,you are the advocate, you are the

voice you are, but even just simplyallowing yourself to live a whole

and full, fully expressed life isa form of activism in this moment.

It's something that is the resultof the work that our ancestors have

(29:04):

done, but to show that you, to letthe people who created the broken

system do the work, because quitefrankly, it's not on us to do the work.

of a broken system.

However, it is on us to be ourselves,wholly, so that we can move the

conversation in the way that we want to.

It doesn't have to be all action.

(29:25):

I just want to put that out there.

One

Pascale (29:26):

thing I'd say about like just being, I just want to

tell two stories really quickly.

The first is when Iwas expecting my son.

Seven, almost eight years ago, I usedto religiously flat iron my hair.

My hair was almost always straight.

That was what professionalismlooked like to me.

That was what beauty looked like.

That's what we were told

Kim (29:44):

professionalism is

Pascale (29:45):

correct.

And so I thought to myself, how can Itell this little one to love themselves?

If they're observing me spendabout three hours every other

Sunday, transforming who I am.

Right.

And not to not have that versatilityand no, no shame to it, but I

found that it was getting inthe way of just being right.

I couldn't go outside when it's raining.

(30:06):

I couldn't work out.

I couldn't do all these things becauseI was trying to subscribe to this.

And so I made a note, he pledgedto my head and no matter what was

happening, whether I was meetingthe president, whether I was

going to be on TV, whatever itis, I had to wear my hair curly.

And it was a tough.

Tough transition time for me to justget to know my hair and my head.

And now like my hair is almostalways in some type of curly, either

(30:29):

pineapple up to, or that's my default.

And so I say all that to say, whenI shared that story, so many people

will come up to me and say, I justspent two hours this morning blow

drying my hair because I want it tobe professional at this conference,

or because I wanted to get this jobat this job, but you just like, Being

up there and talking about it and atfirst I didn't think it was such a big

(30:50):

deal till I told that story one timeand then just the response that I got

said, Wow, that's really important.

The second story I'll say isthat when I actually joined

the number board as historian.

I had just had Xavier, my son,and his feeding time, I was trying

to track with our agenda and wewere completely sliding, like the

agenda was just not agendizingthe way it was supposed to be.

(31:13):

And it just so happened that whenit was my time to do the report was

exactly when my husband at the time wasbringing in my newborn for me to nurse.

So I ultimately was nursing X andreading my report out to the board.

And again, something that I didn't.

I don't think too big about just like,this is his time, this is his meal, I

need him to come get this meal from me.

(31:35):

And this is my time to share the workthat I have been doing for this quarter.

And years later, people are like, oh mygod, Pascal, you being in that boardroom

with your baby just meant so much.

And so there's so manyboard meetings, conferences.

That Xavier is with me a because Idon't want to be apart from him for

so long But also I want people toknow that you can be a president.

You can be a CEO You can be an authoryou can be a very hungry person And

(32:04):

that it's possible and Again, it's justme being but realizing really clearly

that I don't need to subdivide myself.

I'm not a pie that can onlygive this liver or this

percentage that I show up whole.

And sometimes that whole meansa curly fro with my kid with me.

Sometimes that whole is me doing normalwork while I'm at work at my office.

(32:27):

Sometimes that work isprotesting while working.

Like all of these thingsare not about today.

I can only be this part of me.

And that part of me,when I walk into a space.

This is my mission.

And all of these thingsare part of that.

Kim (32:48):

What is your wish for every other woman?

Pascale (32:51):

Is that they have the support they need to show up exactly the way

they are without needing to feel tobe perfect, but just to be themselves.

Kim (33:02):

Be visible.

Use your voice.

Every other woman needs you to lead.

Voice Lessons is co produced,written, and spoken by me.

(33:26):

Kim Cutable.

It's also co produced andedited by Sergio Miranda.

You can find past episodes, shownotes, and the cool stuff our guests

recommend at voicelessonspodcast.

com.

Popular Podcasts

Dateline NBC

Current and classic episodes, featuring compelling true-crime mysteries, powerful documentaries and in-depth investigations.

Stuff You Should Know

If you've ever wanted to know about champagne, satanism, the Stonewall Uprising, chaos theory, LSD, El Nino, true crime and Rosa Parks, then look no further. Josh and Chuck have you covered.

The Nikki Glaser Podcast

Every week comedian and infamous roaster Nikki Glaser provides a fun, fast-paced, and brutally honest look into current pop-culture and her own personal life.